This article focuses on one of Mexico’s most notorious drinks: mezcal.

Since I met Antonio, I knew I was in excellent hands.

His authoritarian tone contrasted with his thin frame. We couldn’t stop giggling after the words he used to reprimand part of the group for not following instructions.

Instead of a stylish uniform, he was wearing faded jeans, white sneakers, and a wide-brimmed hat. His curt, dark-toned skin testified about the years he had been teaching outsiders about the cultural spots in Oaxaca’s central valleys.

In a bright, airy room with glass windows and fabric chairs, after dozens of mezcal samples were ingested, I addressed Antonio for the first time. He was inviting a pair of “chilangas” to join him at the ancient Zapotec ceremonies which take place at night somewhere in the sierra.

“Excuse me, errr, does “mezcal de pechuga” really exists?” I asked with a firm tone after interrupting such a significant conversation.

Antonio’s eyes lightened up and his lips curved into a friendly grin, “Of course, it exists.”

Before he couldn’t continue talking, I added, “Because a lady at the Mercado Benito Juarez told me that was a fallacy created for tourists.”

“Well, it is obvious women does not know a lot about mezcal.”

Even though mezcal is not as famous as Mexico’s other coveted maguey-based alcoholic beverage (tequila), the spirit awakes all sort of passions in the state where is mostly produced, Oaxaca.

Inhabitants have even a saying describing their willingness to have a shot at any moment: “Para todo mal mezcal y para todo bien, tambien” (“for everything bad, mezcal, and for everything good, as well”).

Mezcal is made from the heart (“piña”) of various types of maguey (whereas tequila is made only from blue agave). The piñas are covered while they cook in a pit oven. This underground roasting gives the final product a strong, smoky flavor.

The piñas are crushed and then left to ferment. Some producers add chicken or turkey breasts (“pechugas”) plus fruits and herbs during fermentation or distillation. When that technique is used, the mezcal is called “de pechuga.”

“The turkey breasts give the mezcal a distinctive flavor. Those mezcals sell for more.” Then, Antonio lowered his voice like a kid who is ready to tell you a secret, “But you are not going to find them in a place like this.” Apparently, some mezcals do not have a place at museum-like designated stops.

“You know what, I am going to make a stop at one of my friend’s shop. It’s on the route, anyway.”

When everybody got into the van, Antonio explained he wanted to give us a broader explanation of the different types of mezcal produced in the state i.e. we were going after the hard stuff. Nobody complained when faced with the opportunity of having another round of free samples.

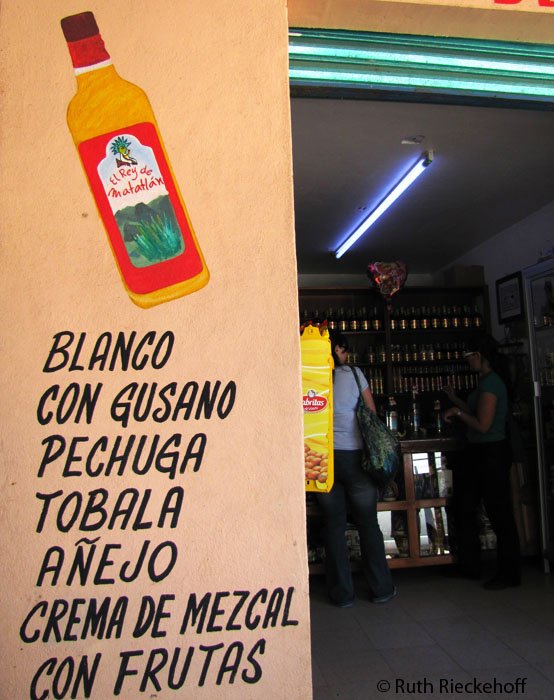

The drive through the semi-desert took only a couple of minutes. We arrived at a small building in the middle of the wide valley. The curvy mountains loomed in the distance. The place was dark and covered top to bottom with dark furniture holding hundred of mezcal bottles. Notes of pineapple, coconut, and coffee were floating in the air.

Antonio greeted the owners and after exchanging a few words, a bunch of bottles started to appear from the “back.” Most of the labels had the Matatlan name in big letters. This town is considered the “World Capital of Mezcal.”

The exchange of samples became frenetic. In here, the owners were not holding anything. Spurts of “anejo” and “reposado” traveled from bottle to cup. A tall lady was having difficulty holding all her pastel-colored, fruit-flavored “cremitas.”

Antonio proceeded to show the color differences between a “mezcal de pechuga” and a fake. Some producers try to recreate the flavor given by the pechuga with a piece of the maguey leave. Antonio said real connoisseurs, like him, could not be fooled.

Antonio also asked the owner to serve his “tobala.” This mezcal is made with a small, wild type of maguey. All efforts to cultivate the variety have failed.

When the members of the group started to move in erratic ways, it was understood that the sampling had to stop. Tours members proceeded to board the van while guarding closely their bags full of mezcal bottles.

“The other day I went to “La Casa del Mezcal” after work. You would not believe the piece of trash they gave me for 70 pesos,” Antonio told me with a disgusted face. “To get a good taste of mezcal, you have to get close to the dry land, the plants and the makers who put the effort in traditional methods. The tartness of the smoke has to burn your throat”.

And that is why Oaxacans hold their favorite mezcal close to their heart, for every bad or good moment.

How to Sample Mezcal

Oaxaca is the land of mezcal. You will find many stores offering samples or selling the drink in the capital (Oaxaca City).

That is a good way to get introduced to the drink but I recommend going to the source, the town of Santiago Matatlan. In there (and in the surroundings), you will find family-run producers offering tours, tastings, and products to the public. In my opinion, visiting two or three of these would give you a better appreciation of what mezcal is all about.

Have you tried mezcal?

Len says

Great blog post! I’ve enjoyed Mezcal for a number of years but had difficulty finding any in Ontario until recently. We now have six or seven varieties available. I’m slowly building a collection.

On my last trip to Mexico I was unable to get to Oaxaca to get any good Mezcal, I only found Gusano Rojo.